The pain of introducing Scrum – or any new workflow for that matter. Obviously we all love the end result: self sustaining teams, better results, faster results and so forth. Introducing (or actually fully adapting and eventually adopting) a new methodology, whether it’s Agile, Lean, Kanban, Scrum or any other, is a painstakingly slow process.

The team that is to adopt a new workflow, but also the whole company, are stuck in their way of handling things as they are. While they might love the promises that adopting a new methodology brings forth, they are not ready for the changes and process that are involved with the change in many of the cases.

Inform your team and your organisation that changing to a new methodology will take a lot of time and a lot of effort. Make them understand that things will not be running smoothly from the get go.

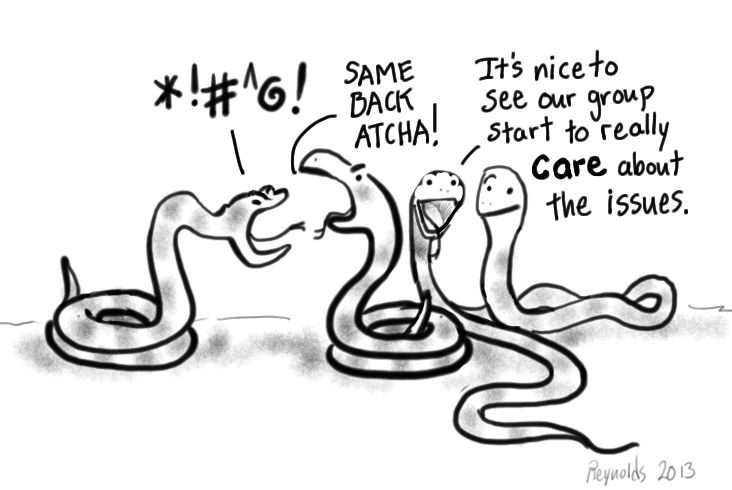

“A team reflects on how to become more effective”

“At regular intervals, the team reflects on how to become more effective, then tunes and adjusts its behaviour accordingly.”

Sources: Agile Manifesto & Twelfth Agile Principle

Scrum, and also other agile methodologies, are built on constant feedback loops. That feedback eventually, time after time, leads to (minor) changes in the way the new workflow is adopted and used.

It is the team that makes Scrum work in the end. It is the team that has to identify and eventually tackle problems and bottlenecks in the current setup. Facilitate and guide the team in the identification and solving of those issues, whether you’re a Scrum Master, a stakeholder or a company as a whole.

Make sure that everyone involved knows that only time and transparency make your implementation work. Make sure that everyone involved realizes that a new workflow takes time to settle in, and mostly that it is a progress, not a straight forward implementation. Any good adoption of a new workflow is one where the team, and the workflow itself, have the space and time to evolve.